The Inuit language is known for having as many as 50 different words for snow. It's no wonder why; snow can be light, heavy, fluffy, sticky, you name it. No two kinds of snow are the same and no two kinds are made the same, and that is especially true for lake effect snow (LES). In a broad sense, LES is made just like any other type of snow or precipitation: by lifting/cooling air until it condenses and falls back to Earth. However, if we carefully dissect just how LES is created, we see that it is truly one of the more interesting types of precipitation.

In order to generate sufficient LES, we first need to make a grocery list of basic elements:

It's possible to create modest LES without all of these ideal conditions, but for the heaviest, most significant snow accumulations, all must come together and work in unison. Each ingredient is important in its own right.

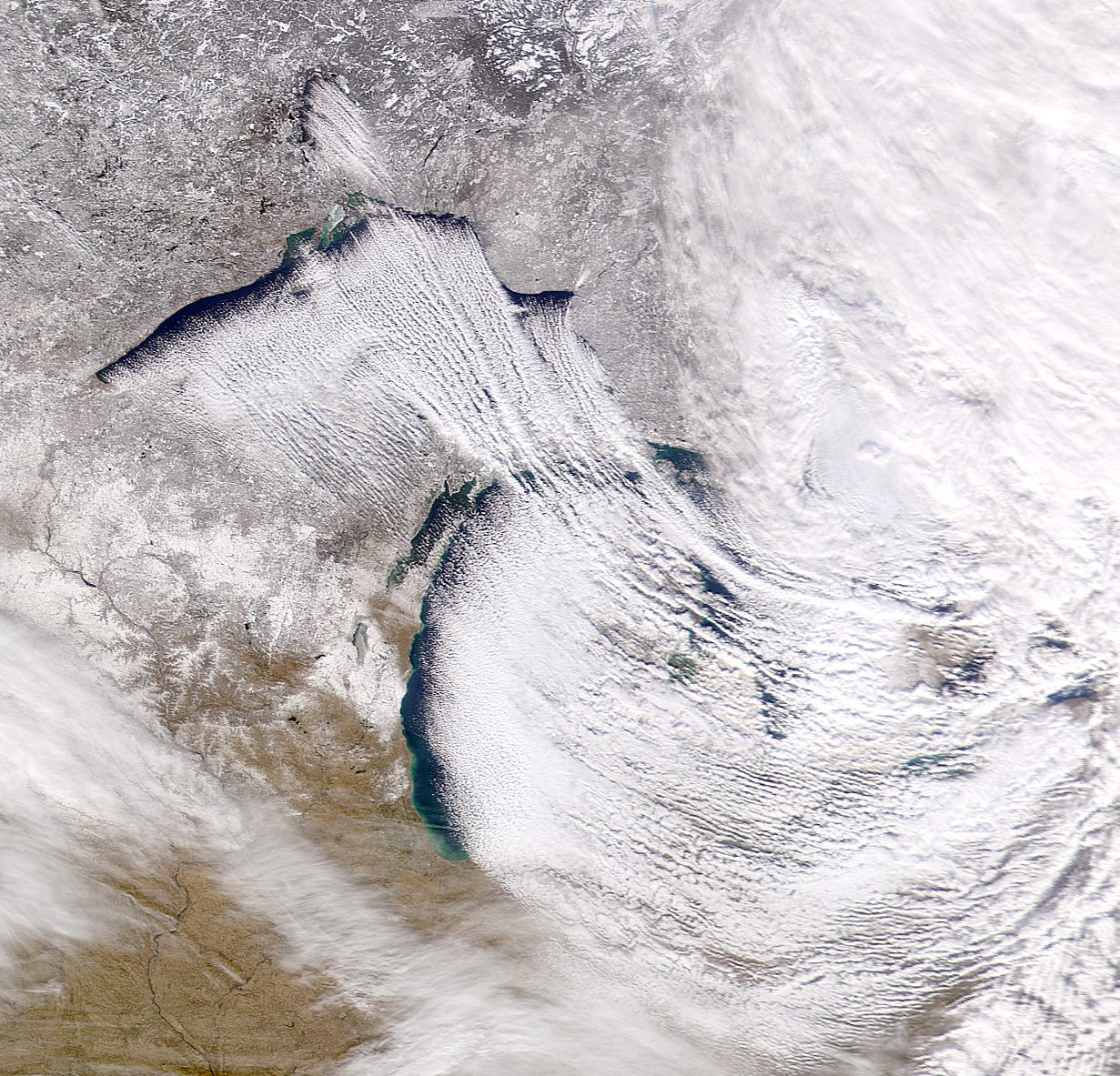

Satellite view of Lake Effect Snow from NASA

The most essential element is the lake itself. After all, it's right there in the name. Snow is mostly water, and that water needs to come from somewhere. Obviously with more water comes the potential for more snow. Thus, the larger the lake, the greater the chances for snow.

Nearly all precipitation is the result of a clash between two air masses, usually warm and cold. LES is a perfect example of such a clash. Oftentimes, lake effect snows occur in the wake of a strong cold front. Ideally, LES needs a 20-25 degree difference between the lake surface temperature and the temperature of the air at approximately 1,200 ft.

LES often occurs in the absence of a major low pressure system. Because of this, the dynamics to create snow must come from elsewhere. This is why the final ingredient, wind, is so important. A bitterly cold air mass can be placed directly over a large body of water, but if the air mass is relatively still, very little snow will be produced.

These ingredients come together to make something called fetch. Fetch is a word for measuring the distance winds travel over open water. Sufficient fetch can be achieved through a number of means. Strong, uniform winds in the lower levels of the atmosphere will yield the greatest fetch. If these winds set up over a large stretch (ideally 60 miles or more) of open water, the fetch increases significantly. However, LES can be created in as little as 20 miles of open water. The fetch potential goes up even further when the air aloft is more than 25 degrees colder than the surface of the lake. Below is a great visual depicting all three ingredients coming together.

It's important to point out that LES can occur in less than ideal conditions. A very cold air mass with very strong winds requires little open water to create snow. Likewise, a modestly cold air mass moving across the entire width of Lake Superior will only require moderate winds to create a few light flurries. Obviously, the combination of all three elements will lead to the best (snowiest) results.